Leaked documents show how Kevin and Ian Maxwell, brothers of disgraced heiress Ghislaine, used a Jersey trust to hide their business activities and finances.

OCCRP

June 17, 2022

The La Hougue Files

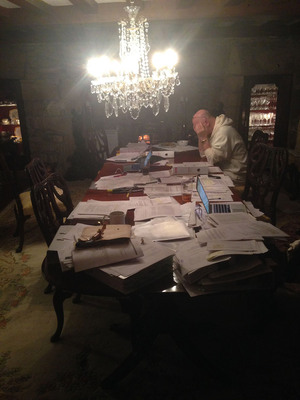

Comprising 350,000 pages, the La Hougue files were discovered on the 58-acre estate of St. John’s Manor in Jersey. Before it was sold in 2020, the manor was the residence of John Dick, a Canadian lawyer and businessman listed in the trust files as La Hougue’s owner.

The cache of documents — spanning the 1980s to 2008 — were unearthed in 2012 by the owner’s daughter, Tanya Dick-Stock, and her husband Darrin Stock. She later sued her father, accusing him of stealing millions of dollars from her family’s trusts and draining them dry.

Bitter legal battles between the Dicks over inheritance issues continue to this day.

Trusts are secretive financial tools that often use a custodian to act as a third party in transactions, such as buying or selling property and assets on behalf of the true owner or beneficiary. By design, trusts like La Hougue make it hard for creditors and even law enforcement or regulators to follow the money.

John Dick admitted the La Hougue files are filled with fraud and criminal conduct, but denied any wrongdoing. In an interview, he confirmed the trust did run out of the manor where he lived, but blamed the operation on La Hougue’s chairman and managing director, who Dick said was acting without his knowledge.

“As far as I know, La Hougue was really being run by Richard Wigley,” said Dick. “A lot of what he did I had very little knowledge of.”

Both Wigley and Dick are implicated in the Jersey files. A letter from Dick’s lawyers found in the La Houge documents from Feb. 10, 2014, identifies him as the beneficial owner of the “La Hougue entities.” Meanwhile, Wigley appears repeatedly in the files directing La Hougue’s activities. In 2018 he testified in a deposition in Colorado that the trust frequently held shares in the names of so-called nominee directors, such as himself.

“We were registered holders of the stock, because Mr. Dick spent his life hiding from his assets and using people and entities so that his name did not appear,” Wigley told the court.

Wigley was sanctioned in 2016 by a U.S. court for committing perjury and he admitted to fabricating documents, including more than $15 million of loan notes for La Hougue. In 2018, a court in Jersey noted in a judgment that Wigley had admitted to “making untrue statements in these proceedings” and manufactured letters, promissory notes and minutes filed as evidence to the court.

In one unusual document from 2002, Wigley instructs staff to burn documents before Dick returns home. He tells them to “hire a commercial shredder and purchase a lot of black bin bags,” adding, “the bags should then be burned at the tip.”

Now in his late 70s, Wigley’s last known address was in Panama, where he opened Pantrust International S.A., a new trust company formed after La Hougue closed. He could not be located for comment.

Pantrust was stripped of its license in December 2014, with the Panamanian regulator citing an “obvious lack of documentation” in customer background checks and accusing it of hiding the names of lenders and borrowers.

Dick, now 84, lives in Newport Beach, Calif., and serves on the board of directors of Liberty Global, a multinational TV and broadband company that owns Virgin Media.

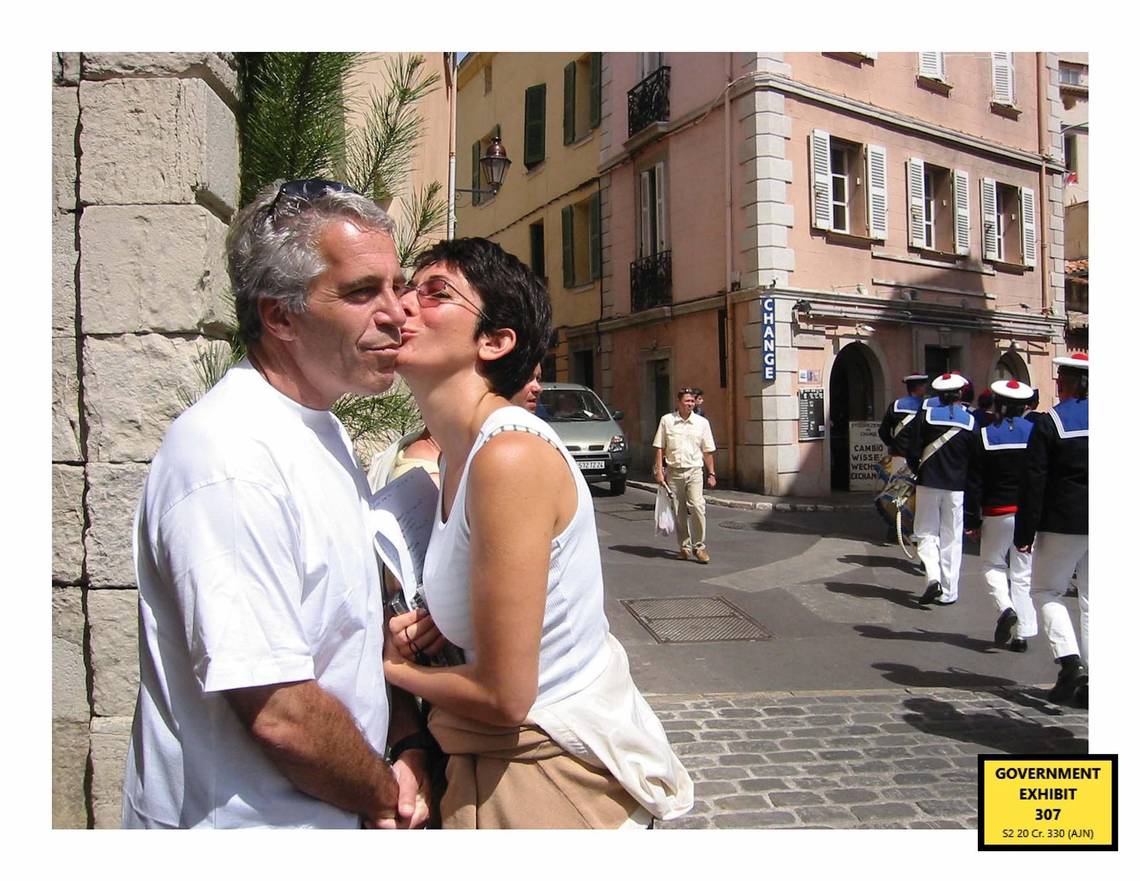

Credit: Evidence from 2021 federal prosecution of Ghislaine Maxwell

Credit: Darrin Stock

Ghislaine Maxwell’s trial and conviction for trafficking minors to pedophile financier Jeffrey Epstein brought her murky finances into the public light, raising fresh questions about her family’s past and the true source of the Maxwells’ sprawling wealth.

A new joint investigation by OCCRP and the Miami Herald examines a trove of documents from an offshore trust that exposes how at least two Maxwell family members and their longtime associates put their fortune into a complex offshore corporate and trust network, likely beyond the reach of creditors and legal adversaries.

The investigation, based on documents from the island of Jersey, a U.K. Crown tax haven, shows evidence of questionable trading activities in publicly listed U.S. companies, secret stock deals, and possible securities violations, while millions of dollars in payments moved through offshore companies to certain members of the Maxwell family.

Reporters found records of secret stock transactions by Kevin and Ian Maxwell while Kevin was the chairman of a U.S. publicly traded company; related-party transactions that may have enriched the Maxwells, but went unreported to the investing public; and the hiding and amassing of major stock holdings by the Maxwell brothers, who share a history of fraud accusations and bankruptcy. These transactions, some of which may have hurt public investors, have never before been reported.

David Leal-Bennett, a U.K. banker to the Maxwells and their companies in the 1990s, alleges the family frequently traded in the markets while grappling with debt, but at the time he did not believe the trades were wrongful. “We saw a lot of shenanigans with shares moving around,” he said. “I could see what they were doing. I told Kevin, ‘You are playing the markets. We do not condone this. You’re going to have to make a choice.’”

The Maxwells are no ordinary British family. Their financial escapades and bankruptcy proceedings have been splashed across the pages of English newspapers for five decades, their marriages and divorces the stuff of national gossip.

The leaked files offer a rare glimpse into how Kevin and Ian Maxwell conducted business through opaque shell companies. These were found buried among thousands of pages of confidential papers discovered at a now-defunct Jersey trust company called La Hougue. The trove was seized by Jersey police in 2015, but leaked to the media, including OCCRP, after authorities on the island took no action.

While these documents provide deeper insights into the financial activities of the Maxwell family, they give just a snapshot of a larger global financial picture that reaches beyond Jersey to other countries and secrecy jurisdictions. Almost everyone involved with the Maxwells on the tiny island has faced investigation, regulatory sanctions, or a long history of litigation.

Just as Ghislaine Maxwell headed to trial late last year, OCCRP and the Miami Herald learned that an anonymous whistleblower complaint was filed with the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) alleging stock trading violations and other concerns involving Kevin Maxwell and La Hougue from the late 1990s to the early 2000s. The SEC would not comment on such filings, or whether it has opened an investigation.

The La Hougue files include the names and signatures of Kevin and Ian Maxwell, detailing payments to their siblings, spouses, and in-laws. Many records of the deals were deliberately concealed in the files, including related-party transactions that moved through complex webs of companies and legal entities across multiple jurisdictions. Some stock purchases were spread among the family and their associates, allowing them to stay just under regulatory reporting thresholds.

William K. Black, a lawyer and academic who rose to fame during the late 1980s as a litigator for several U.S. federal regulatory bodies, noted the files contained “obvious, super-well-known” red flags.

The transactions and trades took place at a time when a U.S.-based telecommunications company co-founded by Kevin Maxwell, called Telemonde, was cited by U.S. regulators for reporting violations.

Black reviewed many of the documents obtained by reporters and said the use of opaque shell companies to buy and sell publicly traded stocks, including those of Telemonde, combined with the involvement of multiple family members in related transactions, were not necessarily proof of criminality but were warning signs.

“Nepotism simply is a major risk and, even if it wasn’t fraud, you would be concerned as a regulator if you saw a lot of these transactions,” he said.

The Maxwell family’s ties to La Hougue appear to trace back to at least early 1997. By the time the trust closed in Jersey by mid-2008, and shifted clients to another trust in Panama, its files chronicled several years of hidden financial activities by multiple members of the Maxwell family.

There is no definitive proof that Kevin and Ian Maxwell, or their family members, broke any laws and they have not been charged with any crime. The brothers declined to discuss details of the Jersey documents, but provided a statement to the Miami Herald and OCCRP.

“Neither I nor my brother Kevin, to whom I have spoken, have any unaided recollection of a company called La Hougue and certainly were not involved as investors, shareholders, directors, agents, or representatives of that company,” Ian Maxwell wrote in an email. He acknowledged they had some “dealings” with La Hougue agent George Devlin “mainly involving loans,” but said he had “no recollection of specific details.”

When reporters sent him multiple La Hougue files revealing details of the brothers’ relationship with the trust, Ian abruptly ended the discussion. “I have not read them and do not intend to,” he said.

A family representative declined to provide further comment on behalf of Ghislaine Maxwell or other family members.

Trusts, Busts, and Hidden Millions

Since the 1991 death of Ghislaine Maxwell’s father, British media mogul Robert Maxwell, questions have swirled over whether the family secreted away chunks of his fortune. His body was found off the coast of the Canary Islands after he mysteriously disappeared from his yacht, the Lady Ghislaine.

Following his death, Maxwell’s youngest sons, Kevin and Ian, were accused by creditors of helping him plunder as much as $1.2 billion from the family’s media empire, including the pension funds of U.K. media company the Mirror Group. Facing a slew of civil actions, Kevin Maxwell filed what was at the time the largest bankruptcy in U.K. history.

A 407-page report in 2001 by the U.K. Department of Trade and Investment on the Mirror Group collapse faulted Kevin for his support of his father’s business practices. It specifically said he knew regulatory filings “lacked frankness,” pointing out the Maxwells had used stocks as collateral for loans, something seen also in the La Hougue documents.

While the brothers were eventually acquitted of criminal conspiracy and fraud charges in 1996, the family’s fortune has remained the subject of speculation ever since.

During Ghislaine’s New York sex-trafficking trial, the public learned how she traveled the world, cavorted with politicians and celebrities, and owned luxury real estate, despite not holding a conventional job for two decades. Public records and court documents show Ghislaine also established a network of complex trusts, companies and non-profit organizations that concealed her wealth, often putting others’ names on their paperwork instead of her own.

U.S. District Judge Alison Nathan denied Ghislaine four separate requests for bail, complaining she could not get “a clear picture of Ms. Maxwell’s finances and the resources available to her.”

Throughout the trial, Ghislaine’s brothers, Kevin and Ian Maxwell, as well as her twin sisters, Isabel and Christine Maxwell, rallied behind her in a public show of support. That may not be solely due to sibling affection: OCCRP and the Miami Herald’s investigation shows all of them received stock or unorthodox financial transfers detailed in both the La Hougue and SEC files.

Credit: REUTERS / Alamy Stock Photo

The Maxwells’ biggest paydays appear to have come between 1998 and 2004, when Kevin co-founded and launched Telemonde. In a story widely covered in UK media, Kevin Maxwell dodged a second bankruptcy in 2004 (not the last one he would sidestep), by settling with a creditor. Yet throughout this period, the La Hogue files show he and his brother privately bought and sold shares in Telemonde and another U.S. tech company, often using proxies, in trades that experts said raised concerns.

These publicly traded U.S. companies saw their valuations soar during the dot-com boom, before crashing and going under. The documents show trades worth thousands and sometimes millions of dollars, though it’s unclear exactly how much the Maxwells made in total.

Based in Delaware, Telemonde bought and sold bandwidth capacity used in wireless communications, opening sumptuous offices on New York’s Park Avenue and in London’s Portman Square. Through a series of acquisitions, it expanded into Bermuda, Switzerland, and Oman.

Starting in the spring of 1999, shortly after Telemonde first went public on a Nasdaq platform for startups, millions of dollars of company shares were sold offshore via La Hougue. The stocks, exchanged through entities controlled by the Maxwells or their agents, were traded both on public exchanges and in private, off-exchange transactions.

As Telemonde’s chairman, Kevin Maxwell earned a salary of $396,000 and reported holding a 4.4 percent stake in the company, according to a 1999 SEC filing. But the fine print of the same filing shows he and his then-wife, Pandora Maxwell, would be able to acquire millions of shares through a British Virgin Islands company holding a 40 percent interest in Telemonde. The couple also had access to shares through a third company in which Kevin held a 33.4 percent interest, suggesting he may have controlled more stock than what could be seen on paper.

When Telemonde’s stock price climbed in the summer of 1999, taking its valuation into the hundreds of millions of dollars, the documents show the Maxwell brothers making furious sales, with funds routed through La Hougue and payments made to family members.

By the year’s end, Telemonde’s stock price had tanked as the dotcom bubble started to burst, with the documents showing the Maxwells again rushing to liquidate shares. For more than 18 months, on- and off-market sales continued, with more than 2.3 million sold in tranches ranging in size from 250 to 220,000 shares.

In early 2000, Robert Maxwell’s wife, Elisabeth “Betty” Maxwell, along with his daughter, Isabel, and Ian Maxwell’s ex-wife, Tara Maxwell, acquired a combined 810,500 shares. They bought them for one-thousandth of a U.S. cent each between March and May, a fraction of the shares’ then market price, which frequently traded above $1 during this period. In violation of exchange rules, these purchases were reported to the SEC more than a year after the family acquired the stock. The SEC filings don’t indicate how family members acquired the shares at such an attractive price or why.

A Family Affair

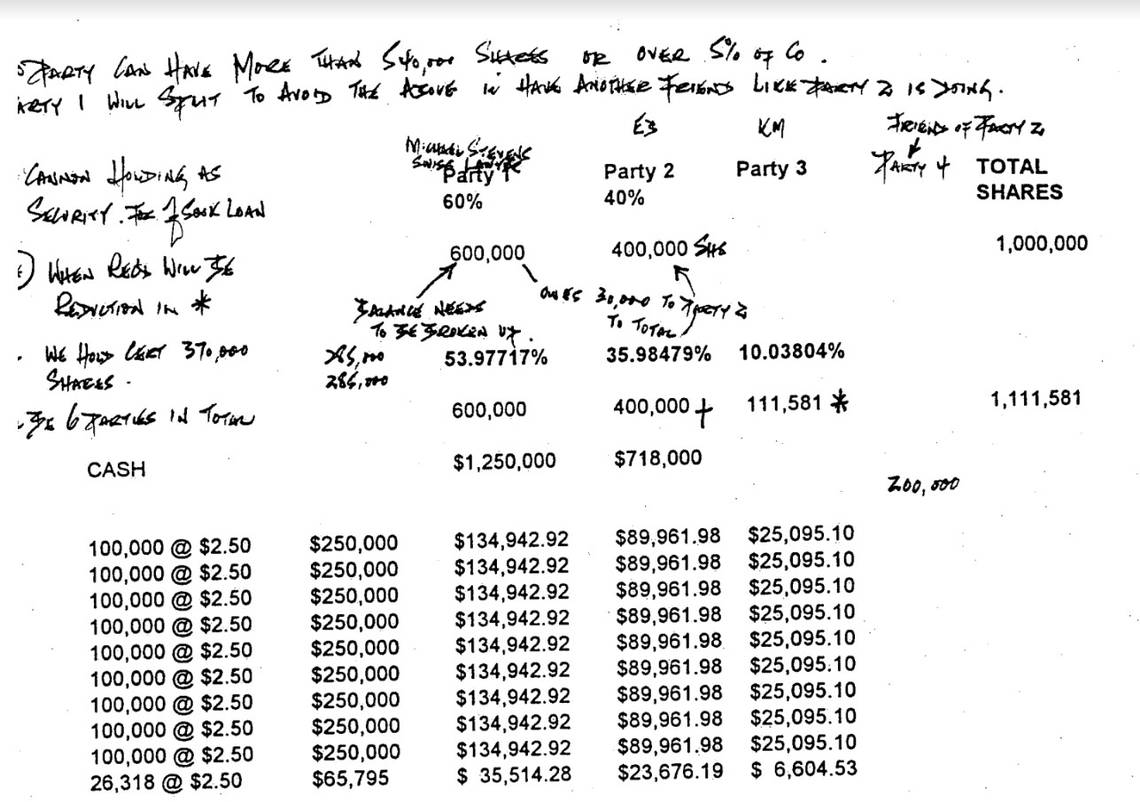

In addition to records of share transactions, the Maxwell files include what securities lawyer Daniel Berger, a partner at the Philadelphia law firm Berger Montague, called “score sheets,” indicating where funds and stocks are going and to whom.

In one series of stock sales and other transactions from July 1999 to July 2000, the files detail approximately $1.2 million of financial flows for an account labeled “Loan 1.” The account shows payments sent to and from trusts, bank accounts, and entities around the world, naming Maxwell family members as recipients, among them:

- $30,354 sent to Christine Maxwell’s husband, American astrophysicist Roger Malina.

- 175,000 French francs, or about $27,400 at the time, to Villeneuve Automobile SA with the reference “Meynard,” the maiden name of Robert Maxwell’s wife.

- $41,600 sent to a Piper Jaffray bank account in Minneapolis directly referencing Kevin Maxwell.

- $155,800 sent to another account with the reference “Westbourne.” Westbourne Communications Ltd. was founded by a former staffer of Robert Maxwell, and hired Kevin Maxwell as a consultant before he became Telemonde’s chairman in May 1999. Ian Maxwell also worked at Westbourne Communications.

Alongside the rapid liquidation of Telemonde stocks, Kevin and Ian Maxwell bought and sold shares of another publicly traded U.S. company called NetJ.com during the dot-com era. From early 2000, when NetJ spiked to a high of $7.44 a share, to when its stock price crashed to pennies in 2001, La Hougue arranged multimillion-dollar deals trading hundreds of thousands of shares in both companies on behalf of the Maxwell brothers.

Notes scribbled by a La Hougue agent in the margins of one of the files warn that allocating 5 percent or more of outstanding shares in a company to any one shareholder involved should be avoided, lest it trigger a mandatory SEC report.

“The 5 percent rule comes up a lot in stock manipulation,” said Danny F. Dukes, a former bank executive and forensic accountant who reviewed the files, calling it a “hallmark” of U.S. stock fraud.

Exactly how much members of the Maxwell family made on these trades is not clear. But the share deals went on for years and the La Hougue documents indicate they ran into multiple millions of dollars.

As Telemonde and NetJ failed amid the bursting of the so-called tech bubble, their stock prices plummeted to pennies and never recovered. The La Hougue documents show trades on behalf of the Maxwells continued apace as the companies failed.

Between early 2000 and early 2001, the documents indicate the Maxwells’ trades grew from batches of tens of thousands to hundreds of thousands of shares. Because these companies were now trading at pennies per share and at low volumes, any big trades by the Maxwells likely would have swayed the stock prices.

Credit: PA Images / Alamy Stock Photo

Credit: Darrin Stock

A

t the same time, Telemonde’s management sought to issue enormous amounts of additional shares, citing a lack of capital, and proposed increasing the number of company shares from 145 million to 475 million, according to an SEC filing in 2001.

Like Robert Maxwell’s media empire, Telemonde cratered under an avalanche of debt. In its annual report to the SEC for 2001, the company stated it no longer had enough capital to meet its financial commitments, noting that this “could jeopardize our existence.”

“We have incurred operating losses and a negative cash flow since our inception,” the company said in the report, adding that by the end of that year those losses had reached $189 million.

By March 2002, Telemonde’s accountant Moore Stephens warned bluntly in a quarterly report: “There is substantial doubt about the ability of the company to continue as a going concern.”

Telemonde’s heyday was short-lived, but it languished for years. In 2005, the SEC revoked its market registration, citing “egregious” failures to file required public reports that “deprived the investing public of current and accurate financial information on which to make informed decisions.”

The SEC added that “many publicly traded companies that fail to file on a timely basis are ‘shell companies’ and, as such, attractive vehicles for fraudulent stock manipulation schemes.”

“When you look at these documents, a lot of these companies seem like layered shams,” said Frank Casey, a Wall Street risk manager who examined the Maxwell files at Stock’s request. Casey was on the team that first attempted to blow the whistle on Bernie Madoff’s infamous Ponzi scheme.

Debts, Proxies, and Anonymous Files

British solicitor Malcolm Grumbridge and La Hougue agent George Devlin appear to have facilitated many of the Maxwells’ stock transactions from 1999 to at least 2001.

Now deceased, Devlin was a well-known British private investigator and legal consultant involved in defending a member of the “Guinness Four,” defendants in a major 1980s stock-manipulation scandal involving the famous beer company.

“I never acted for La Hougue, or really had anything to do with them other than following the instructions of my clients,” Grumbridge said, who explained he was representing the wishes of Kevin and Ian Maxwell.

No Maxwell family members were ever included on La Hougue’s official client list, but were kept in a set of unmarked files under Grumbridge’s name, said Darrin Stock who, along with his wife, discovered the hidden Maxwell papers within the Jersey documents late last year.

“We could never find the Maxwells or Epstein in there, but we also knew the most sensitive clients were in the anonymous files,” he said. When he and his hired team of forensic accountants searched for Grumbridge, they found the details of his dealings with the Maxwells.

Grumbridge said he worked closely with Robert Maxwell from 1976 until his death, and continued to handle financial and property affairs for the Maxwell brothers and Ghislaine Maxwell until 2020. He also appeared in leaked records of Epstein’s black book, which contained the names of friends and business associates.

In a rare interview with OCCRP and the Miami Herald, Grumbridge acknowledged his longtime ties to the Maxwells, but declined to discuss business specifics, citing client confidentiality.

“I was an external adviser,” he said, adding that he no longer does legal work for Kevin and Ian Maxwell, but stays in touch with them on a non-professional basis. He said he only met Epstein once at a social event and he’s never had contact with Dick, La Hougue’s beneficial owner. Beyond that, he said, “Regrettably I am unable to comment.”

U.K. banker Leal-Bennett, who worked closely with the Maxwells and testified against the brothers during their criminal trial, told OCCRP that Robert Maxwell admitted to him that the family was moving money through “ultra-private” offshore entities. Leal-Bennett managed the family’s day-to-day corporate and personal finances from 1989 to 1991.

“Robert Maxwell was clearly controlling everything and Kevin was his first lieutenant,” Leal-Bennett recalled. “Kevin was hard-nosed, while Ian was more of a soft touch.” Robert and Kevin actively managed the money, he said, while Ian remained in the background. “They would bend the rules to their advantage,” he said.

Notably, the Maxwells’ accounts and funds are often represented in the La Hougue files as “loans,” including where funds or shares are being transferred. Because loans are not taxable and profits are, experts said it is possible the funds were simply labeled as loans to avoid paying taxes.

Some loans went unpaid and, in multiple correspondences, Devlin can be seen chasing the Maxwells to repay debt, as well as threatening bankruptcy proceedings. In other times, the Maxwells’ accounts show large, ballooning negative balances skyrocketing for months, at the same time it appears Kevin Maxwell was trying to dodge his creditors.

“It is not normal for accounts at any financial institution, anywhere, to be allowed to run into debt like that for months or years at a time,” said Dukes, the forensic accountant.

Grumbridge said securities can indeed be used as collateral for a loan, but he declined to comment further when pressed for details by reporters about the Maxwells’ loans or debt, citing client confidentiality.

The La Hougue files also show Kevin Maxwell secretly conducted business through a Jersey-based entity called Symposia Holdings Ltd. In 2001, British businessman Collin Sullivan reportedly sued Kevin over a real estate deal, demanding Maxwell document his relationship to Symposia, which had played a pivotal role in the transaction.

Maxwell told the court he did not have any documentation, because he had deleted it, and without this crucial piece of evidence in Sullivan’s case the judge ruled in Maxwell’s favor. But the La Hougue files show Kevin was not only a principal of Symposia, which he secretly used to do business — he also guaranteed its debts.

Reporters were unable to reach Sullivan for comment.

Credit: PA Images / Alamy Stock Photo

“Rreckless-conduct”>eckless Conduct”

The Maxwells used La Hougue’s services until at least 2004, when Kevin dodged another bankruptcy. As the trust closed, Wigley moved some clients with him in 2007 to Panama, forming a new company, Pantrust International.

British regulators banned Kevin Maxwell from running any company in the U.K. for eight years in 2011 after he and two directors transferred 2 million British pounds to companies related to them from a construction company shortly before it collapsed.

Kevin and Ian have faced a bankruptcy again in the U.K, as recently as 2016. Their older sister, Isabel, once a dotcom millionaire, was also reportedly declared bankrupt in 2015 by the U.K.’s High Court.

Even before Kevin Maxwell’s ban on running U.K. companies was lifted in 2019, Grumbridge set up a real estate company for him called Avenue Partners Developments Limited.

In a December 2020 settlement with the U.K.’s Solicitors Regulation Authority, Grumbridge was fined by the authority and agreed to leave the legal profession after admitting to years of “reckless” conduct. He resigned from Avenue Partners in January 2021, with Kevin becoming an active director in the company again in 2020. The company remains active today.

Failures in record keeping and conflicts of interest were noted by the U.K. Solicitors Regulation Authority and Grumbridge admitted to risking “facilitating dubious transactions that could have led to money laundering.”

The regulator specifically denounced how Grumbridge acted for “two brothers simultaneously with one file and one client ledger,” without identifying the brothers. Asked if those were the Maxwells, Grumbridge did not directly confirm it, but added: “There’s been so much written about me and the Maxwells over the years that I don’t know of any other brothers.”

Grumbridge cropped up one more time — at Ghislaine’s trial. In the lead-up to the proceedings, U.K. daily The Times revealed he had managed some of her financial and property affairs, including the London home where Ghislaine and Prince Andrew took a snapshot alongside Virginia Giuffre, the Epstein victim who later accused the prince of sexually assaulting her.

The land registry documents for Ghislaine’s home in fact listed Grumbridge as the custodian, underscoring his closeness with her. Grumbridge confirmed to reporters that he was the custodian, but tried to distance himself from the disgraced heiress.

“Obviously I haven’t spoken to Ghislaine in a very long time,” he said.

The La Hougue files were first reported on by New Zealand investigative journalist Nicky Hager, who shared them with global media outlets.