As Wealth Inequality Soars, One City Shows the Way

Leah McGrath Goodman

Newsweek

September 24, 2015

JIM URQUHART FOR NEWSWEEK

Tom Christopulos steers a black Nissan Armada through the sharply angled streets of Ogden, Utah, a historic metropolis about 35 miles north of Salt Lake City lodged at the base of the towering Wasatch Mountains, dissecting the neighborhoods home by home and crunching the numbers out loud. As part of his drive-by, he canvasses the terrain voraciously, even compulsively, visually cataloguing every detail—a rite he’s performed for nearly a decade. “I know every block in this town, every house,” he says. “See those mansions over there on Jefferson Avenue? They were cut up long ago, turned into rentals—flophouses, really. We bought them up, renovated them and turned them back into single-family homes.”

JIM URQUHART FOR NEWSWEEK

Born and reared in Ogden, Christopulos has labored for the past eight years as the town’s director of community and economic development, squeezing prosperity—slowly and painstakingly—from abandoned rail yards, slaughterhouses and run-down buildings in an effort to rebuild Ogden’s middle class. “It’s been real pick-and-ax work,” he says.

Today, Ogden, with a population of roughly 86,000, boasts a distinction that has put it on the national radar: At a time when the United States—along with much of the rest of the world—is grappling with the pernicious effects of ever-widening wealth inequality, Ogden has become an unlikely beacon of egalitarianism. The city, together with its neighboring communities, has the narrowest wealth gap among America’s largest metropolitan statistical areas, according to the U.S. Census Bureau’s five-year American Community Survey.

But just over a decade ago, the future here looked bleak. Ogden’s main streets were deserted, its shopping districts lay in ruins, and vagrants roamed downtown, peddling drugs. An online message board from 2009 decried Ogden’s urban wasteland and reputation for being “a low-class gang-infested area,” adding despairingly: “Sadly, the Ogden mentality is so deep-rooted” that any efforts to revitalize the town were opposed, and “pursuit of change has offended” many.

Driving this past summer with Christopulos and his economic team, one could not help but be awed by the beauty of this stretch of land at the western edge of the greater Rocky Mountains. Yet just before us were dilapidated rail tracks, a harsh reminder of the city’s glorious commercial past. These days, steel-and-glass aeries rise from the rusting, crumbling infrastructure, punctuating the prosperous present landscape. The story of how Ogden got here is a valuable lesson for a country struggling to bridge the chasm between haves and have-nots.

JIM URQUHART FOR NEWSWEEK

Traffic travels under a sign on Washington Boulevard in Ogden, Utah, August 17. The city, together with its neighboring communities, has the narrowest wealth gap among America’s largest metropolitan statistical areas, according to the U.S. Census Bureau’s five-year American Community Survey.

‘The Defining Issue of Our Time’

Over the past several years, renowned libertarian and former Federal Reserve chief Alan Greenspan, outspoken billionaire Warren Buffett and presidential candidates have come to the same conclusion: Ordinary Americans are no longer getting a fair shake. In the aftermath of the 2008 financial crisis, Greenspan described the emergence of two different Americas—”fundamentally, two separate types of economy”—one in which the wealthy had made a “significant recovery” and the other in which the bulk of America’s labor force remained in a financial rut.

This year, Republican presidential candidate Jeb Bush called the growing divide “the defining issue of our time,” stepping up the rhetoric. “More Americans are stuck at their income levels than ever before,” he said. While the causes of the trend are the subject of endless debates, the statistics don’t lie. Since 1979, real earnings have risen 17 percent, according to the Economic Policy Institute, a nonprofit, nonpartisan Washington think tank. Such slow growth makes it tough for most Americans to pay the bills, let alone accumulate any wealth.

Yet Americans turn on their TVs and watch U.S. Treasury Secretary Jack Lew hailing the nation’s impressive economic growth, which he recently called one of the world’s only “bright spots.” That disconnect can be jarring, says Joseph Stiglitz, professor of economics at Columbia University and winner of the Nobel Prize for economics, because “for many, the middle-class lifestyle is no longer in reach.”

ANDREW BURTON/REUTERS

Police officers monitor an Occupy Wall Street protest outside the New York Stock Exchange in New York March 30, 2012. Anger at income inequality inspired the Occupy Wall Street movement, which spread across the country but changed little.

The consequences for society go beyond dollars and cents. While research on the interplay between economics and social patterns is still relatively new, says Stiglitz, he notes that it shows “more and more people are exhibiting patterns of social dysfunction”—delaying marriage, buying a home and having children; or raising a family as a single parent—behaviors, he says, that “used to be an attribute of families who were at or below the poverty line” and yet now are encompassing anyone who’s not wealthy.

Stiglitz says rising inequality is not so much the result of natural forces of capitalism but what he calls an “ersatz” capitalism in which a “predatory” few at the very top put more effort into “getting a larger slice of the country’s economic pie than into enlarging the size of the pie” for all.

Lest the ultra-wealthy think this won’t matter to them, recent research from Barry Cynamon and Steven Fazzari, released in conjunction with the Institute for New Economic Thinking, shows that rising income inequality may be the primary reason for the nation’s lethargic economic recovery. They point to a 17 percent drop in household demand, compared with pre-recession numbers.

The Great Gatsby Curve

In a groundbreaking study released by the National Bureau of Economic Research, Emmanuel Saez, professor of economics at the University of California, Berkeley, and the director of its Center for Equitable Growth, and Gabriel Zucman, assistant professor at the London School of Economics, pinpointed when U.S. wealth inequality began its upward climb: 1978.

Related: Obama Focuses on Income Inequality in State of the Union Address

Although the average real growth rate of wealth per American family between 1986 and 2012 was 1.9 percent, that number was skewed by the nation’s richest 160,000, who saw their real wealth grow 5.3 percent per year from 1986 to 2012. By contrast, for the bottom 90 percent in the U.S., there was no wealth growth at all.

This is a sharp reversal of the prosperity trend that saw the bottom 90 percent of America’s earners go from holding 20 percent of the nation’s wealth in the 1920s to 35 percent in the mid-1980s, according to Saez and Zucman. As of 2012, the bottom 90 percent had fallen back to holding just 23 percent.

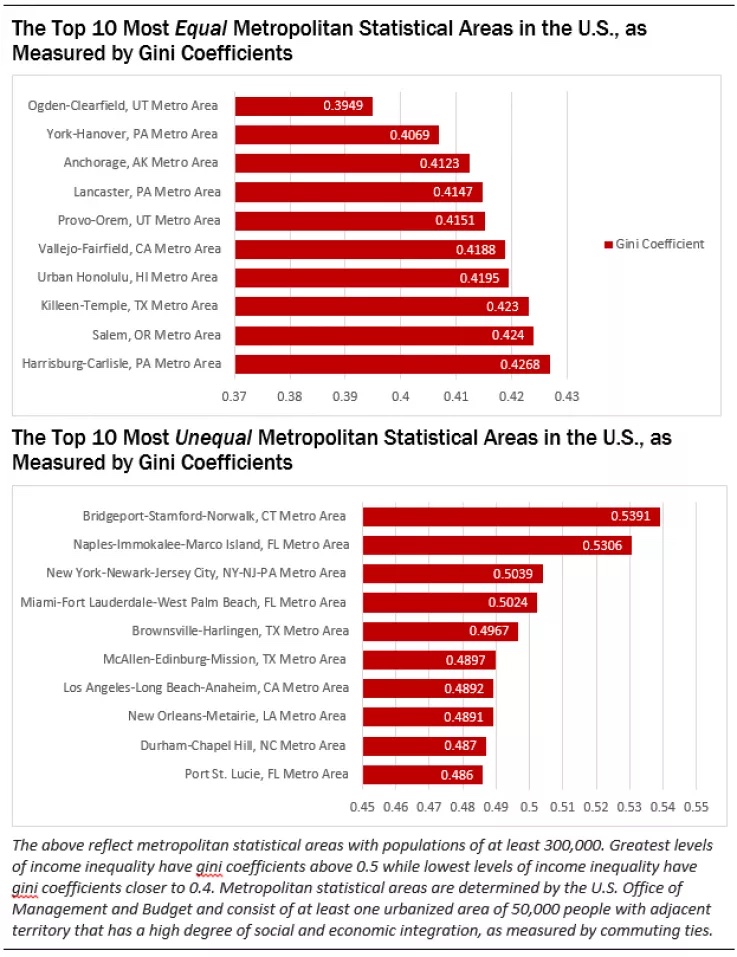

Zoom to enlarge. Full width version available here.

Meanwhile, America’s 160,000 richest families more than tripled their share of the nation’s wealth, from 7 percent in 1978 to 22 percent in 2012, representing a level not seen since America’s peak years of inequality 1916 and 1929. “It is a very concerning trend,” says Marjorie Wood, senior economic policy associate with the Global Economy Project at the Institute for Policy Studies, a Washington think tank focusing on social justice issues in Washington. She likens the wealth gap to the coming of a second Gilded Age, but one that differs from the first in that much of today’s accumulated wealth is not ostentatious. “In the past,” she notes, “there were a lot more public protests because wealth back then was so much more visible.”

The very notion of rising inequality is offensive to many Americans, because it counters the American dream and the widely held notion that we live in a land of equal opportunity. Yet it’s a problem researchers in Washington have known about for years. In 2011—the year Greenspan acknowledged the emergence of two Americas—Miles Corak, professor of economics at the Graduate School of Public and International Affairs at the University of Ottawa, laid bare the troubling relationship between inequality and social mobility in his paper “Inequality From Generation to Generation,” later dubbed by the White House “the Great Gatsby Curve.”

Corak’s research showed that the family an American child is born into greatly affects that child’s future earnings. His international rankings of the countries with the worst intergenerational mobility included Chile, the U.K., Italy and the U.S. (in that order). Countries offering the best intergenerational mobility were Denmark, Norway, Finland and Canada. Countries falling somewhere in the middle were Spain, Japan, Germany and New Zealand. “There is a disconnect between how Americans see themselves and the way the economy and society actually function,” he wrote. “Many Americans may hold the belief that hard work is what it takes to get ahead but, in actual fact, the playing field is a good deal stickier than it appears.”

Yellen has taken a lot of heat from critics who contend the Fed should stay out of matters of income inequality, arguing it is too political. She fired back, stating, “Economic inequality has long been of interest within the Federal Reserve System” and is of increasing concern to Americans.

‘Grotesque and Immoral’

With another election cycle revving up in the U.S., Americans are hearing the same bromides as in past seasons from presidential candidates of both parties. Democratic front-runner Clinton is trying to make fixing inequality a cornerstone of her campaign, observing that “the deck is still stacked in favor of those at the top.” Bush recently acknowledged, “If you’re born poor today, you’re more likely to stay poor.”

CITY OF ODGEN

Ogden’s historic 25th Street shopping district was once a rundown shell reminiscent of many of the U.S.’ main streets in decay, but is now once again a bustling part of the city.

Vermont Senator Bernie Sanders, a longtime independent now running for the Democratic nomination, has been denouncing the nation’s wealth gap since Nixon was in office, when he wrote that 2 percent of Americans held more than one-third of the nation’s wealth. Sanders stated, “A handful of people own almost everything…and almost everybody owns nothing.” That was in 1973. More recently, he has advocated a federal minimum wage of $15 an hour by 2020 (right now, it’s $7.25), but other candidates have been slow to second that proposal.

Related: Many More Americans Seen Spending More Than Half Their Income on Rent

If income inequality remains sky-high and the bottom 90 percent cannot start to accumulate wealth again (remember that their gains have been close to zero from 1986 to 2012), the resulting disparity will destroy decades of progress, warn Saez and Zucman. “That is to say, 10 or 20 years from now, all the gains in wealth democratization achieved during the New Deal and the post-war decades could be lost,” they contend. “While the rich would be extremely rich, ordinary families would own next to nothing, with debts almost as high as their assets.”

All of which raises the fiendishly difficult question: What if the inequality problem is too big for any one leader—or team—to fix? Perhaps, rather than unpacking and debating its bottomless nuances, it might be helpful to examine a community, preferably of substantial size, that has already identified and successfully solved many of these problems.

Waitresses Buying Houses

For the purposes of this article, Newsweek looked at the latest wealth data from the U.S. Census Bureau’s five-year American Community Survey for major metro areas with surrounding communities of at least 300,000 residents. The widest wealth gap in America, according to that data, can be found in three Connecticut cities: Bridgeport, Stamford and Norwalk—known as American hedge fund country for the crush of millionaires and billionaires settled in their environs, many of whom work in nearby Greenwich. Second place for widest wealth gap was Naples, Florida, which included the upscale Immokalee-Marco Island. The third covered the combined area of New York City plus Newark and Jersey City, New Jersey.

NEWSWEEK

The top 10 most equal and unequal metropolitan statistical areas in the U.S., as measured by gini coefficients.

How does Ogden compare with Connecticut’s hedge fund country? The richest 20 percent of Ogden’s households hold around 40 percent of the city’s income. By contrast, in the metro area covering Bridgeport, Stamford and Norwalk, the richest 20 percent hold close to 60 percent of the income.

Ogden does not simply have the narrowest wealth gap; this middle-class oasis also offers many residents higher wages and a lower cost of living than the national average, with some of the lowest unemployment and best job growth numbers in the country. It’s the type of place most Americans had assumed disappeared in a cloud of cynicism somewhere between Studio 54 and Reaganomics.

Mark Muro, a senior fellow at the Brookings Institution and the director of its Metropolitan Policy Program, co-authored a report in June listing Ogden as one of “the hottest 15 metros for advanced industries,” a city that has worked hard to attract jobs in high-growth sectors. In particular, Ogden’s focus on technical jobs and vocational training for its nonuniversity graduates has made it a U.S. hub for science, technology, engineering and math (also known as STEM) jobs, Muro says.

While the number of university graduates in Ogden is less than half its adult population, the town has installed numerous STEM programs in its schools and single college, Weber State University, that match students and adults with high-tech employment opportunities—and technical training starts as early as kindergarten, says Terrence Bride, Ogden’s business development manager. This leads to higher-paying jobs for graduates without the need for a four-year university degree, which means lower debt for graduates and ultimately a chance to accumulate wealth.

“I came here from California with my husband, who’s an aerospace engineer,” says Carrie Vondrus, who owns a retro clothing shop in Ogden’s downtown. “The low cost of living allowed me to stay home and raise my kids, which we couldn’t have done where we were living. Now my 25-year-old son just bought a five-bedroom house in town. He is a manager at Dick’s Sporting Goods, and it’s his first home. He and his girlfriend are paying for it by themselves.”

Stories like this abound in Ogden, where the median age is 30 and even restaurant waitstaff are buying houses—for many, the first step toward accumulating wealth. While the city’s median income is still below the national average, at $35,844, its growth is led by the high-tech job sector, which according to Brookings pays an average annual salary of $60,580 a year.

Perhaps most significant, Ogden did not start out this way. Throughout the 1990s, the town was mired in seemingly intractable problems not unlike those facing the nation today: crumbling infrastructure; a lack of stable jobs with good wages and benefits; a shortage of affordable, quality housing and schools; and an increasingly frustrated population that, nonetheless, was deathly afraid of change.

“It took us 50 years to figure out that doing nothing was a lot riskier than doing something,” Christopulos, the city’s economic development director, tells Newsweek. “For a long time, nobody could agree on what to do. We found out the price of doing nothing was the loss of millions and millions of dollars in tax revenue and decay. It wasn’t until we hit rock bottom that we finally got the consensus we needed to change.”

Until the 1960s, Ogden was a thriving railroad town, the junction of the once-warring Central Pacific and Union Pacific railroads, which reached a détente in 1869 with the planting of the golden spike that joined the two lines at Promontory Summit, just northwest of Ogden, to create the nation’s first transcontinental railroad. So great was Ogden’s wealth at the turn of the century, it boasted “more millionaires per capita than any city in the country,” according to Mayor Mike Caldwell.

But with the rise of the interstate and the decline of the railroads, Ogden lost its status as northern Utah’s primary commercial hub—and its wealthy denizens fled. Between 1960 and 1990, Ogden hemorrhaged thousands of people and millions of dollars of business. By the late 1990s, the city was in dire straits, its once-resplendent downtown in a shambles and its 25th Street shopping district vacant.

The turnaround began in 2002, with the election of 29-year-old Matthew Godfrey, at the time one of the youngest mayors in the U.S., who spent the next decade tearing down and rebuilding the city’s downtown—often over protests—and courting businesses to move to Ogden, which he tried to rebrand as a mecca for high-tech talent. “I was young, and we had a really ambitious agenda, and I don’t think that many people thought we could pull it off,” he says.

“At first, there were no takers. Our tech industry was virtually nonexistent. We were just this dirty, run-down old railroad town,” says Godfrey, now 45. “Businesses would come in, look around and then relocate to Salt Lake City or somewhere else. So we gave up on the high-tech firms and started to recruit outdoors companies full bore. And when they started to come in around 2008, suddenly the high-tech firms were interested. Suddenly, we were this hip, cool outdoor-recreation town.”

Meanwhile, Christopulos, who worked under both Godfrey and his successor, Caldwell, had begun buying back polluted land, industrial buildings and trashed neighborhoods, cobbling funds together wherever the city could. “My team and I created our own kind of Skunk Works to bring together whatever we needed to do a project, from federal and state grants to financing to contractors to environmental remediation,” he says.

By 2007, their efforts to attract commercial tenants to Ogden’s newly renovated historic buildings started to pay off, generating millions of dollars in revenue for the town in the form of tax increments, property leases and sales taxes, which it reinvested in more projects and improvements. To date, the town has generated more than $4 billion of new tax revenue.

Critical to the master plan was a vibrant downtown. After rotting for decades, Ogden’s historic 25th Street, where Al Capone used to bootleg liquor, was recently listed as one of the most beautiful thoroughfares in America for its amphitheater, festivals and street art. (The town’s planning manager, Christy McBride, says the downtown, now 95 percent occupied, hosts around 650 events a year, attracting tens of thousands.)

Other than Albuquerque, New Mexico, Ogden was the only major metro area in the West to post job growth in 2009, while the recession was still raging throughout the rest of the country. It was one of the first cities in the nation to return to its prerecession peak output that same year. And before the recession, Ogden’s high-tech job sector had grown 12.6 percent from 2002 to 2007.

Today, Ogden hosts a diverse group of expanding businesses, with advanced industries representing around 26,500 jobs, according to Brookings. Its employers include Northrop Grumman, Rossignol, Universal Cycles, Mercury Wheels, U.S. Foods, Amer Sports, Cornerstone Research, Home Depot, Hart Skis, ConAgra Foods and Hershey’s.

A sign in front of Ogden’s highest peak proclaims in great, arching letters: “It pays to live in Ogden.”

A Solution Beyond Politics

While every town is different, and there are limits to how even the best growth strategies might be applied elsewhere, what happened in Ogden can happen elsewhere. Professor Raj Chetty of Stanford University, one of the world’s foremost economists and currently a visiting professor at Harvard University, says while policy solutions at the state or federal level can offer a better overall environment for economic growth (by improving access to college, for instance), a person’s hometown can have the greatest impact on chances for upward mobility.

Parsing big data from cities across the U.S. with a team of other researchers as part of the Equality of Opportunity Project, Chetty found that the city where a child is born affects his or her chances for upward mobility in life enormously. According to the project’s data, released earlier this year, a child from a lower-income family in Ogden would make $2,440, or 9 percent, more annually by age 26 than the national average. The same data also show that Weber County, where Ogden is located, offers greater income mobility than 76 percent of the counties in the U.S. “The local level is of significant interest, because it’s an area where I think there might be more tractable policy solutions,” Chetty says. “Federal or state policy is unlikely to be the entire solution, because it seems like the problems are different in different places and require a more tailored approach.”

By working as a community to increase overall prosperity, Ogden has moved past the economists’ discussion about how to redistribute existing wealth to focus on attracting new wealth by cultivating businesses that offer higher labor income to its residents and enlarging the “pie” described by Stiglitz.

Higher labor income, plus a lower cost of living, leads to a greater savings rate and wealth accumulation. Perhaps this period is not the end of the American dream, says Christopulos, but only marks its redefining. “From a philosophical standpoint, we would just as soon find a way to create more overall wealth and raise the level of all income,” he says. “That is more related to economic opportunity than a gap between the rich and the poor.”

Surveying Ogden’s downtown, Christopulos glowers at another row of houses he’d like to gut, refurbish and release back into the neighborhood. “We try to use economics to try to figure out how to effect social change, but it is hard,” he says. “Unlike Uncle Sam, I cannot increase the money supply. We don’t have those kinds of control elements. Each situation is different and has so many parts. There is no one-size-fits-all solution.”

Whatever the solution is for the country, Christopulos says he’s pretty sure it will have nothing to do with politics—and especially not with partisanship masking the real divide: financial inequality.

“I’ve been a Republican and I’ve been a Democrat,” Christopulos says. “Now I’m a communitarian.”